Segmann - Ice Stream Height

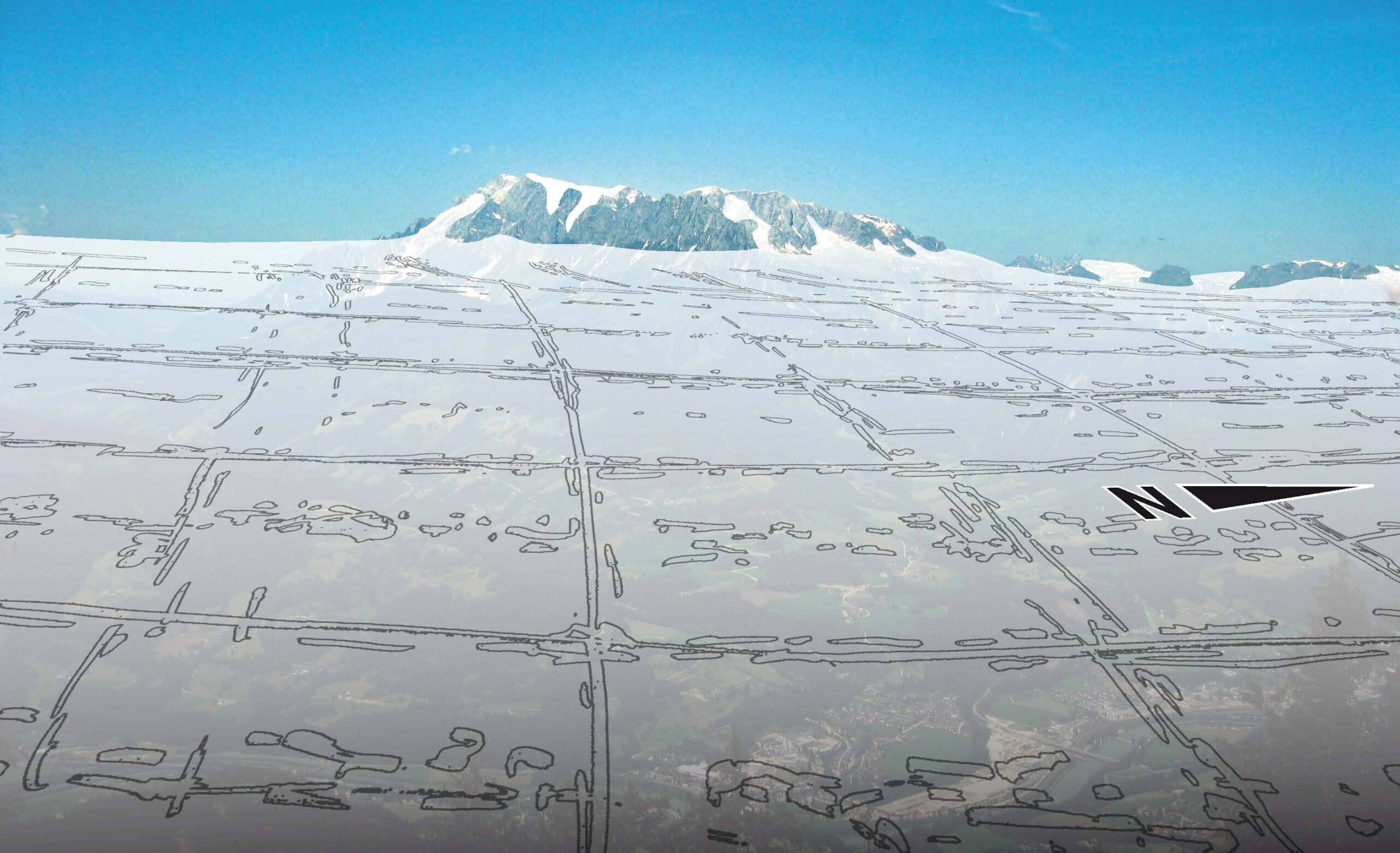

At the peak of the Würm ice age, 24-22,000 years ago, the Salzach glacier filled the Salzach valley. Only the mountains, crests and ridges higher than 2,000-2,100 m protruded from the ice flow. Everything below was covered by the ice masses.

The thickness of the ice masses was immense! The valley floor of the Salzach river was cleared and deepened by the eroding effect of the ice flowing away.

Drilling showed the solid rock at the mouth of the Großarler Ache river into the Salzach river 45 m below today's level; at the Kleinarler Ache river, it was more than 78 m and at the Fritzbach river, it was more than 50 m below today's level. The ice age valley floor, which is also the base of the glacier, was 45 to 100 m lower than today.

By contrast, the highest erratic finds - these include e.g. crystalline rocks found in the Northern Calcareous Alps and do not fit here geologically - are at 1,920 m (Gamerith & Heuberger, 1999). This is a granite gneiss block weighing around 500 kg on the way from the Erichhütte (1,545 m) to the Taghaube (2,159 m). From this, we can measure the vertical extent of the high ice age glaciation in the geopark at approx. 1, 400 m.

Kids

Setting fire in the mine

A long, long time ago, miners extracted valuable ores in the mines. However, there were no large machines to help people with their work. So they had to work with fire in the mine. The fire-setting method in mining was an old technique in which miners built large fires with piles of wood on the rock faces in the mountain to heat the rock. The subsequent cooling with water caused the rock to crack, making it easier to break. This method was used before machines and explosives were available. However, it was dangerous due to the development of smoke and the lack of oxygen in the mine.

Setting fire in the mine

The fire-setting method of mining was a dangerous technique used many centuries ago to break through hard rock in the mountains. Imagine you are a miner deep underground and you have to work your way through rock-hard cliffs to get to valuable treasures such as silver, copper or gold. But back then there were no big machines or explosives like today. So what to do? The miners had a clever idea: they used fire to soften the stone!

This is how it worked: the miners built huge fires on the rock faces, which burned hot for many hours. The heat made the rock glow and expanded it. But the really exciting part came when they suddenly poured cold water over the hot rock! This caused the rock to cool rapidly, contracting and cracking open with a loud crack. These cracks made it much easier for the miners to break the rock with their tools.

Setting fire in the mine

The fire-setting method in mining was an old but very effective technique that was mainly used in the Middle Ages to break through hard rock. At that time, there were no machines or explosives, and miners had to come up with clever methods to get at valuable raw materials such as gold, silver or copper that were hidden deep in the rock. One of these techniques was fire-setting.

The idea behind it was relatively simple, but effective: first, large fires were lit on the rock face in the mountain tunnel. These fires burned for hours and heated the rock. The heat caused the rock to expand, creating small tensions in the rock. The decisive moment came when the fire was extinguished and cold water was poured onto the hot rock. The sudden cooling caused the rock to contract rapidly, creating cracks. These cracks made the rock unstable, making it easier to break with tools.

Although this method was effective, it was also very dangerous. The smoke and heat in the narrow mine tunnels meant that there was often a lack of oxygen, which made the work risky. In addition, the rock could break and fall uncontrollably, which posed an additional danger to the miners.

Today, firesetting is no longer used as there are modern machines and explosives that work more safely and quickly. Nevertheless, it is fascinating to imagine how miners used fire and water to utilise the forces of nature to access the earth's treasures.